Improved varieties help both growers and agricultural sustainability

The following article originally appeared on February 11, 2019, via agnewscenter.com

Ames, Iowa (AgPR) — Proso millet could become a key crop in water-limited areas now that its genome has been sequenced, opening the door greater and more rapid yield improvements than in the past. An international consortium of Chinese and American public sector researchers and Dryland Genetics announce publication of the genome of proso millet (Panicum miliaceum) in the journal Nature Communications.

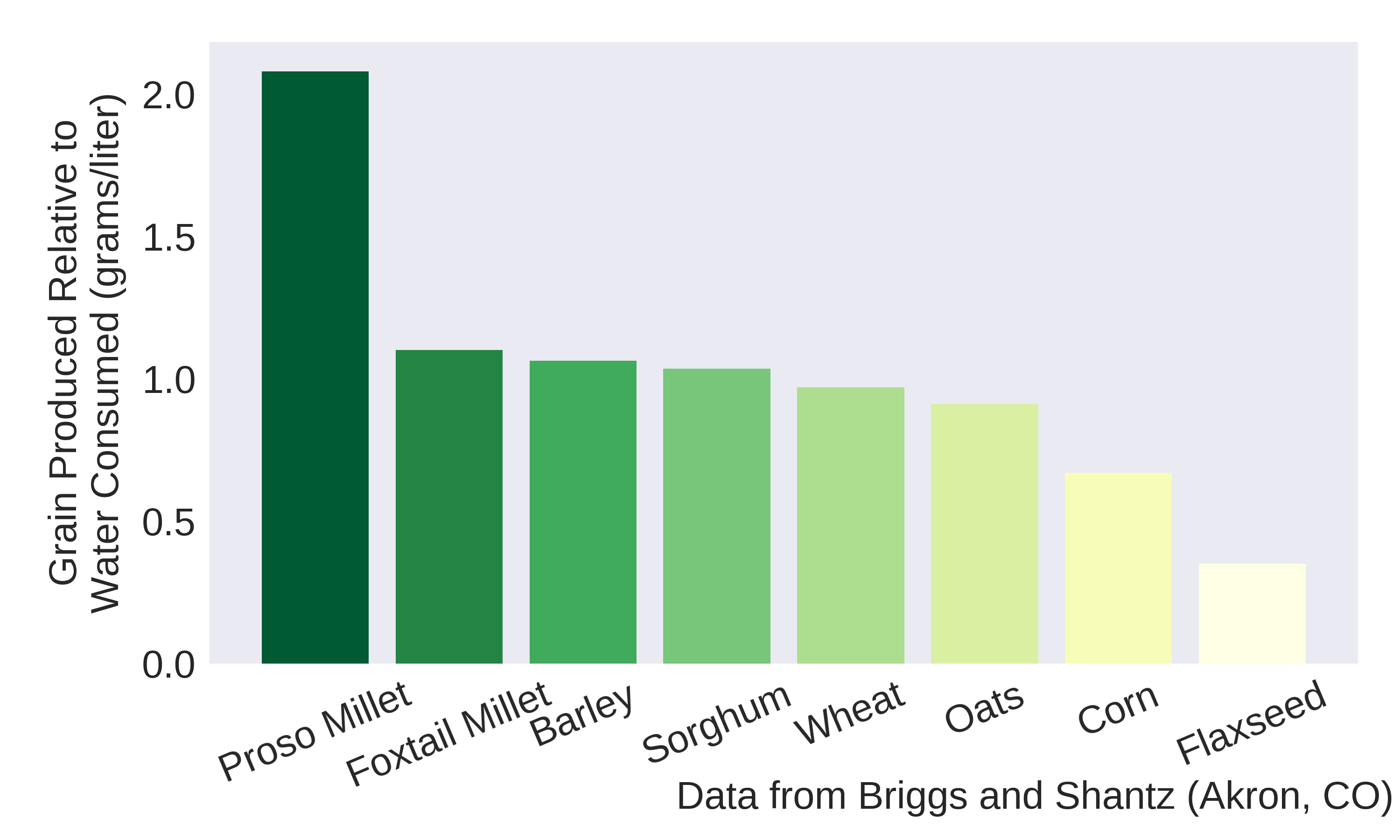

Proso millet’s strong suit is its ability to grow with less water per bushel produced than any other cereal crop – and even on poor-quality land. One of the earliest crops to be domesticated, archaeological evidence suggests the crop was first grown by farmers in Northern China more than 12,000 years ago. It then spread across Asia and Europe along the earliest trade routes, finally reaching North America with early European settlers.

The sequencing of the proso millet genome has enabled Dryland Genetics to use modern statistical genetic breeding tools to develop new, more productive varieties of proso millet. It also is anticipated that this new genome sequence will accelerate the development of varieties adapted to new regions.

“Living in Nebraska, the limits of the water supply are never far from my mind,” says Dr. James Schnable, one of the founders of Dryland Genetics and an author on the present study. “A lot of people have put a lot of time and effort into trying to make corn use less water while producing the same amount of grain. Our idea was to instead identify a crop that already uses water efficiently. It turns out it’s much easier to make a water-use-efficient crop higher yielding than to make an existing high-yielding crop, like corn, use water more efficiently.”

Approximately 500,000 acres are planted with proso millet in the US each year, primarily in those portions of Colorado and Nebraska where farmers lack water for irrigation. Only six varieties have been developed in the past 30 years and only two of these – Huntsman and Sunup – are adapted to much of Colorado. The newly sequenced genome makes it straightforward to identify hundreds of thousands of genetic differences among diverse proso millet varieties collected from all over the world, enabling Dryland Genetics to select lines to mate with each other to produce new varieties adapted to any particular part of the world, whether the High Plains of the United States, Inner Mongolia in China, or the Caspian Steppes of Ukraine.

Dryland Genetics Co-Founder Dr. Patrick Schnable explains, “This technique of genomic selection is being widely used in corn breeding to enhance the rate of genetic gain per year. Dryland Genetics has used genomic selection to achieve double-digit percent yield increases of proso millet in the High Plains.”

|

“It is becoming increasingly urgent to develop new crops that can thrive in semi-arid conditions, given increasingly variable rainfall and competing demand for existing water from agricultural and urban use,” Schnable adds.

Dipak Santra, an associate professor at the University of Nebraska Panhandle Research and Extension Center says, “This will have a huge potential impact on the region’s rural economy. Proso millet’s direct value to (the semi-arid High Plains of the United States) is $45 million/year, but considering its benefits to the dryland production systems, the total value of proso millet to the region’s economy could be closer to a billion dollars.”

Proso millet has a high nutritive value similar to wheat, rice and corn; is gluten free; is easy to digest; and has a low glycemic index. Hence, the potential exists for much wider popularity.

|

More about Dryland Genetics

Dryland Genetics is Midwest-based startup founded in 2014 that is using its global germplasm collection, genomic selection, and other innovative breeding technologies to develop more productive proso millet varieties to increase agricultural productivity and, profitability, and the stability and sustainability of the global food supply. For more information, visit www.drylandgenetics.com.

Frequently Asked Questions About Proso Millet

Question: Why is publication of the genome for proso millet an important development?

Answer: The proso millet genome is important for breeders around the world because it will make it both faster and easier to test each individual new plant we develop for tens of thousands of genetic differences and identify which differences in the genome predict how plants will behave in a farmer’s field. Essentially this genome is going to allow us to develop a 23andMe for proso millet.

Question: Dryland Genetics has elected to increase proso millet yields through conventional breeding methods. Why?

Answer: Developing and releasing a new genetically engineered variety of a crop is a long and expensive process. The estimates I’ve seen put the cost at more than $100M per variety including development, testing and regulatory approvals, and it can take 10-13 years. When we talked to proso millet growers, we learned the need for new varieties is urgent, and that they value the markets that are open to them because there are no genetically engineered varieties on the market. We don’t want to do anything to put those markets at risk.

Question: Now that the proso millet genome is available, will Dryland Genetics and others use genetic engineering to increase proso millet yields even more rapidly than conventional breeding methods?

Answer: At Dryland Genetics we have no plans to employ genetic engineering to develop new varieties of proso millet. It’s important to remember that conventional breeding brought corn yields from about 30 bushels/acre in the 1930s to 120 bushels/acre in the 1990s without the application of genetic engineering.

Question: What are the benefits of proso millet as a food crop? Feed crop? And, bird seed?

Answer: As both a food and feed crop, the greatest benefit of proso millet is its sustainability. This is a crop that can grow in incredibly dry parts of the world without requiring any irrigation. From a nutritional standpoint, proso millet is a lot like corn or sorghum, but with a little more protein and a little less starch.

Question: Why is proso millet so popular as a birdseed?

Answer: Because birds really, really like it. A lot of cheaper birdseeds have big red seeds in them, which are milo or grain sorghum. To limit bird damage in the field, milo has been bred to be distasteful to birds. This has not been done to proso millet which is both a blessing – birds really love to eat it from a bird feeder – and a curse – birds also really love to eat proso millet when it is growing in farmers’ fields.

Question: What are the economics of growing proso millet as a food crop? Feed crop? And, bird seed?

Answer: The market for bird seed is limited, but also quite price insensitive. So, in a year when there is a shortage of proso millet, prices can sky-rocket, while in regular years the price of proso millet grain tracks the price of corn or sorghum quite closely. With current grain prices, a farmer might be making only $20-40/acre after all expenses and depreciation, but this is on farmland that sells for maybe $600/acre, not the $6,000-$10,000/acre seen in the middle of the Corn Belt. The University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Extension office offers a publication that goes into the economics of growing proso millet in detail. (http://extensionpublications.unl.edu/assets/pdf/ec137.pdf)

Question: How profitable can growing proso millet be compared with other dryland crops?

Answer: Given the yield of current varieties, proso millet makes the most economic sense for farmers who can grow it in rotation with wheat. Proso millet uses so little water that it can help the ground water recharge so there is more moisture for the subsequent crop of wheat. However, when new, higher-yielding varieties come on the market, these economics are likely to change. Depending on the specific year, a 10% increase in yield might translate twice as much net profit per acre for farmers.

Question: Is proso millet gluten free? And, if so where can it be used to replace wheat flour?

Answer: Proso millet is much more closely related to sorghum and corn than it is to wheat, so it is gluten free. It’s starting to show up in more and more gluten-free products, from gluten-free bread to gluten-free beer. In 2018, about half the newly introduced food products containing millet were baked goods, but it’s also being incorporated into snack foods and breakfast cereals.

Question: Where can US growers sell proso millet? Are contracts available?

Answer: Some farmers grow proso millet under contract, and there are many grain elevators in Colorado, Nebraska, and South Dakota that buy proso millet. However, the crop used to be grown in other states where water is a big limitation on agricultural production, but growers we’ve talked to stopped growing it because they had to drive many hours to elevators that would buy it. As irrigation water becomes scarcer, however, there is increasing interest in growing proso millet again among farmers in places like Kansas. Once proso millet makes it to grain elevators, it is shipped all over the US and exported around the world.

Read the article at agnewscenter.com